We need to get serious about tackling the UK’s toxic combination of low growth AND high inequality

Politics should be a public service vocation: it is about what the country needs, not just what you’re about. The question all politicians running, or seeking to run, a country should answer is “what is the central challenge facing the nation in that time and that place”. It’s also the question they should ask themselves, because election campaigns are as much as exercise in the public working out which party understands the job to be done, as they are a competition between different policy programmes to do it.

Asking this question is particularly important when countries have major challenges to overcome – and that is where the United Kingdom finds itself in the 2020s. So, as a new Prime Minister takes office and a Labour Party looks ahead to the next general election, let’s step back to the big picture of where our nation is.

Great Britain is in relative decline

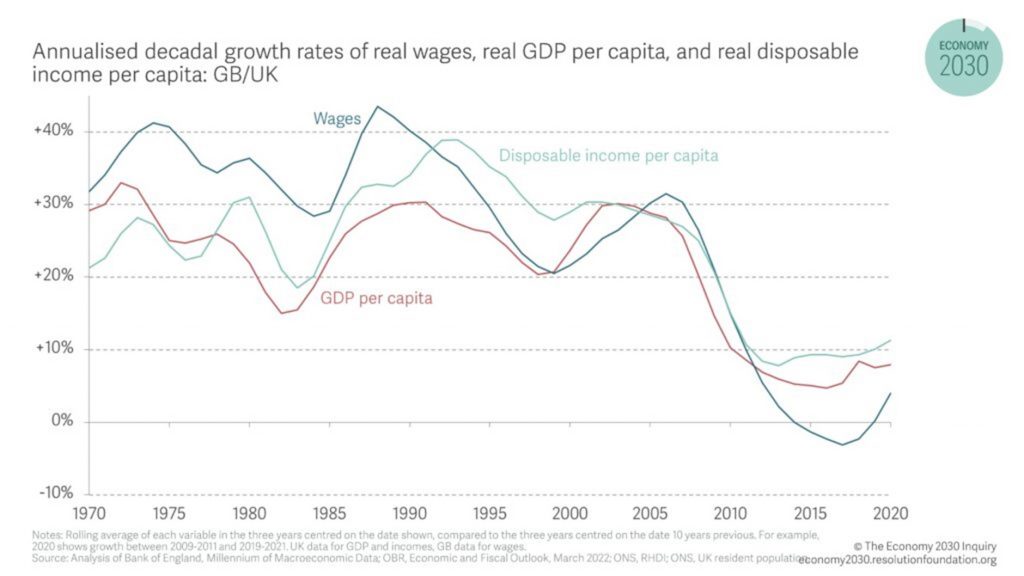

We’re a great country – the clue’s in the name. But we are also one in relative decline. That’s uncomfortable for politicians to admit, but doing so is the crucial first step in doing something about it. Saying “world beating” over and over again doesn’t help turn around the reality that the world has been beating us over the past 15 years. Most advanced economies grew more slowly post-financial crisis, but we’ve seen half the productivity growth of the 25 richest OECD countries. Having almost caught up with the economies of France and Germany from the 1990s to the mid-2000s, the UK’s productivity gap with them has almost tripled since 2008 from 6 per cent to 16 per cent. When some on the left argue this doesn’t matter because GDP doesn’t feed through to ordinary people’s living standards show them this chart – weak growth is the reason real wages stagnated in the 2010s, having grown by an average of 33 per cent a decade from 1970 to 2007.

This relative decline is why UK households are so poorly prepared for the cost of living crisis rightly dominating politics today. And it’s why we’re combining the highest taxes in decades with record NHS waiting lists.

We need to address the toxic combination of low growth AND high inequality

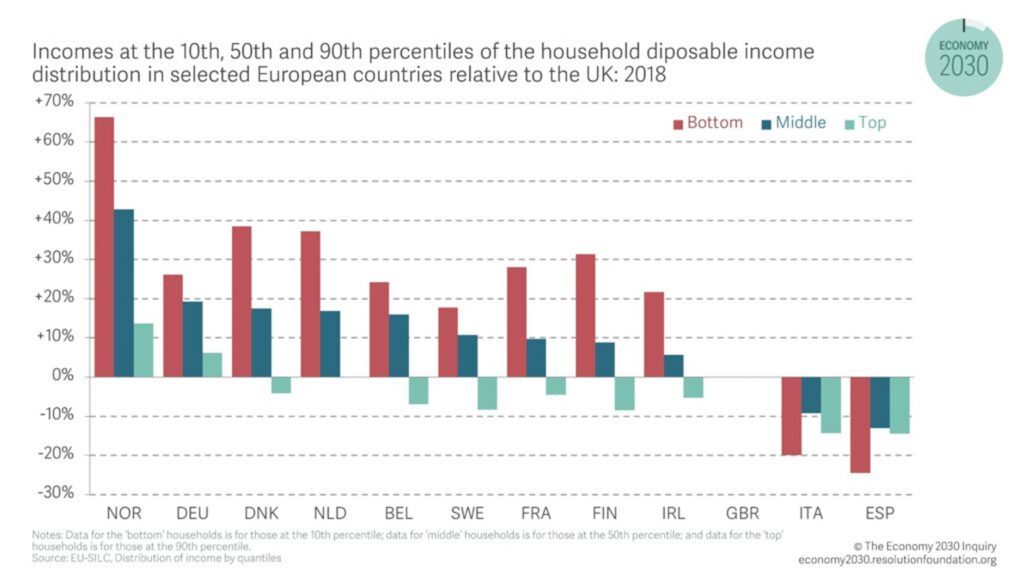

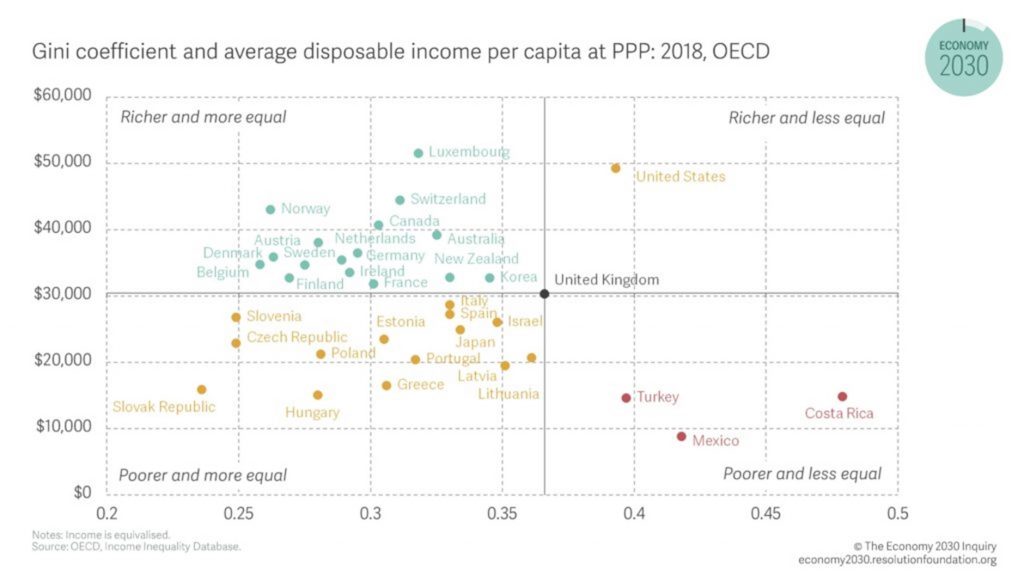

Liz Truss has rightly acknowledged the need to address this low growth disaster. But that is only one of the two central reasons Britain works for so few of its people today. The second is that UK income inequality is higher than in any other large European country, with huge gaps between places as well as people: income per person in the richest local authority – Kensington and Chelsea (£52,500) – is 4.5 times that of the poorest – Nottingham (£11,700).

High inequality and low growth combine with disastrous result for lower-and-middle-income Britain, and younger generations. Our rich are still richer than the rich in most advanced economies, but everyone else – the middle class as well as the poor – are falling behind. The squeezed middle in Britain is now 9 per cent poorer than their counterparts in France. Low-income households in the UK are now 22 per cent (or £3,800) poorer than their French equivalents.

Meanwhile the young have seen generational pay progress grind to a halt. Eight million younger workers have never worked in an economy sustaining average wage rises. Those born in the early 1980s were almost half as likely to own a home as those born in the early 1950s at age 30. We cannot go on like this.

We have to be serious about the nature of our economy, and where growth will come from

The scale of the economic challenges we face leads some to look for silver bullets, or silver linings, to solve our problems. But life is harder than that. Tax cuts won’t end our productivity stagnation: growth isn’t low because taxes are high, taxes are high because our growth is low. Brexit, whatever it’s wider economic/democratic pros and cons, won’t lead to a manufacturing revival. More home working will improve the well-being of high earners, but won’t lead to people living in Lincoln and earning London wages. And the net zero transition will have less impact on GDP than either its opponents or proponents suggest. It’s just crucial to saving the planet.

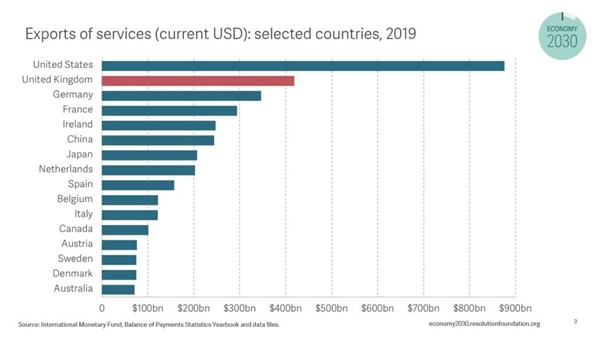

Instead we need to get serious about the nature of our economy and how to make a success of it. We need to stop thinking we’re all about banking, and wishing we were all about manufacturing. The truth is we’re a broad-based services superpower – musicians, architects, programmers and scientists, as well as bankers. Neither main party wants to celebrate it, but we’re the second largest exporter of services in the world.

This isn’t going to change, because countries don’t swiftly shift what they are good at: of the top 10 products the UK was most specialised in back in 1989, seven were in our top 10 in 2019. So, we need to make a success of it. This should drive how we prioritise new trade deals, reject worries about ‘too much education’, rethink corporate tax to encourage investment (including in intangibles) and turn levelling up rhetoric into reality. High-value service industries thrive in cities, but we’ve failed to ensure that enough of our large cities outside London capitalise on that fact.

We must be as hard headed about getting inequality down as growth up

We’re simply not serious about what it would take to turn around high inequality. Businesses mouth warm words about ESG, while half of shift workers receive less than a week’s notice of their schedules. Politicians worry our benefits system is paying some to sit idle, as the number of families experiencing destitution reaches one million.

Not all jobs will exist everywhere, whatever politicians promise, but good jobs should. The minimum wage shows we don’t have to choose between high employment and high standards. Low earners are around three times more likely to experience contract insecurity or volatile hours or pay than higher earners. Higher wages in non-tradable parts of our economy such as social care or hospitality bring with them trade-offs in terms of higher prices, but that is what more equal (and often richer) countries look like.

Each new crisis sees us patching up the welfare state rather than ensuring it is fit for purpose in the first place. The basic level of benefits is now just £77 per week – only 13 per cent of average pay, the lowest on record. Pre-pandemic almost one-third of households with a disabled adult were in poverty, as were nearly half of families with three or more children. There is no route to lower inequality, nor decent society, that accepts this status quo.

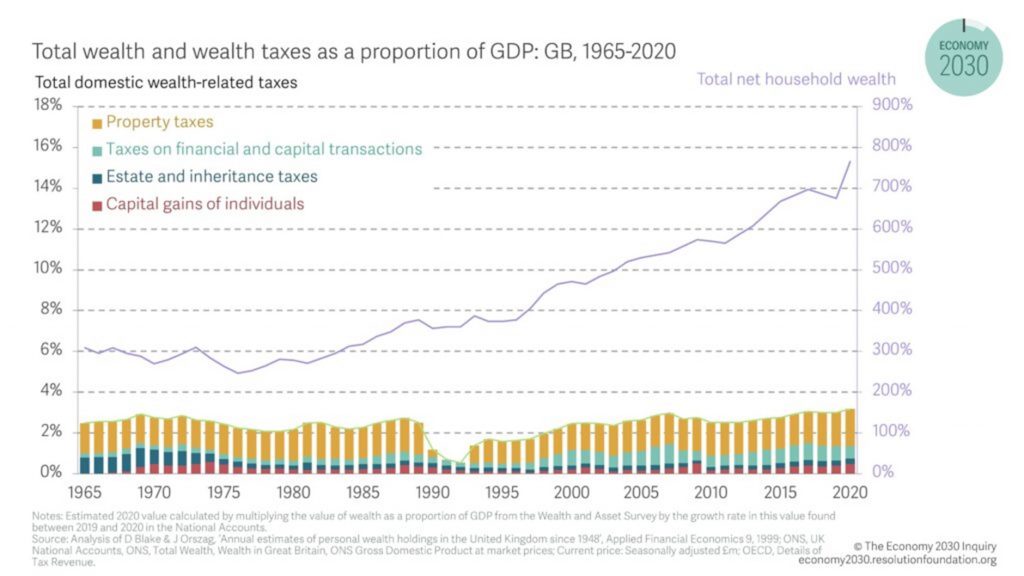

There are political choices about the exact size of the state, but there is no route to a much smaller state that has any popular support given our ageing society, rising healthcare costs, and the new fashion for more defence spending. Remember it was cutting defence from 8 per cent of GDP in the mid-20th century to around 2 per cent today that allowed health and education spend to grow in the past. So, today’s debate about lower taxes should extend to how we get better ones. It’s time for a new approach recognising that wealth has risen from three to almost eight times national income since the 1980s, while wealth taxes have not risen at all as a share of GDP.

Catch-up is possible, and the prize for low and middle income Britain is huge

None of this is easy. But there is one benefit of our recent relative decline: we have huge catch-up potential. Many countries that we used to compare ourselves manage to be much richer, and substantially more equal, than us. The task isn’t to become as equal as Norway and rich as the US, it’s to make steady catch-up progress by moving in a north westerly direction in the chart below.

The prize for doing so is huge, especially for low- and middle-income Britain. Think of a set of what we’d always previously have considered peer economies to the UK: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. We are now 21 per cent poorer than them. They are also all more equal. If we matched both their income and inequality levels incomes would rise by £8,800 per household for the British middle class.

That is the prize, not for transforming the UK into a paradise of American productivity and Scandinavian equality, but from the hard but achievable task of building a better Britain. Whatever you think you came into politics for, this is what politics as a public service in the 2020s should be all about.